Hail and the Meskwaki

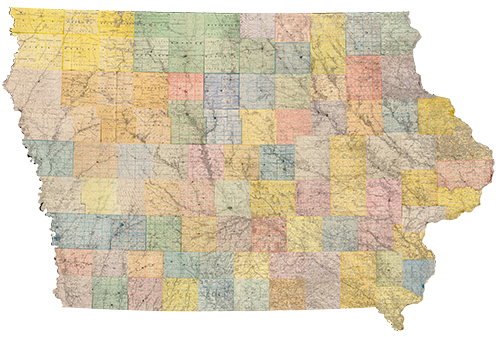

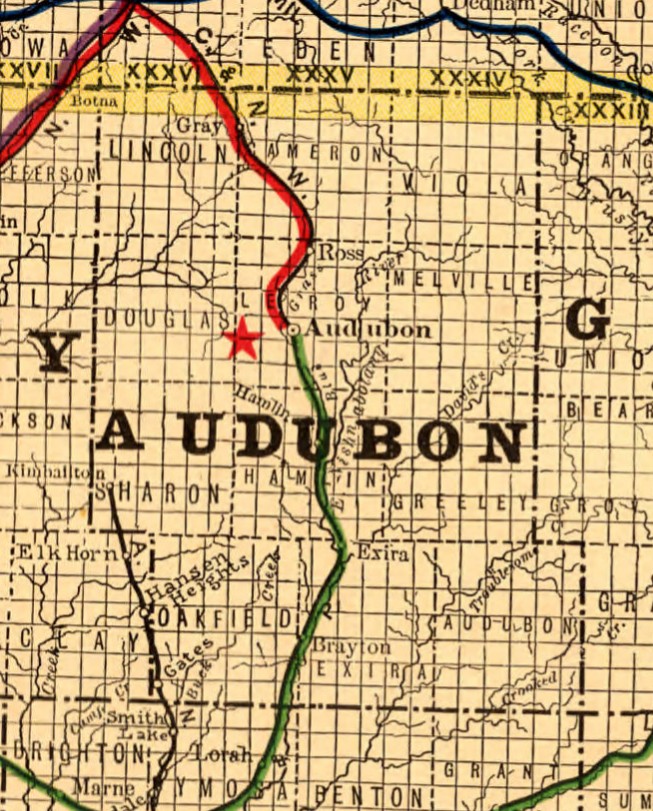

Audubon county, Iowa

Beck O’Brien

8/8/1883

Around seven o’clock in the evening on August 8, 1883, there was a hail storm in Audubon County. In The Fairfield Tribune, the headline described the storm as such: “Rain and Hail. A Terrific Storm of Hail Passes over Western Iowa. Crops Destroyed and One Woman Killed. Hail Covers the Ground to a Depth of Five Feet. The Most Destructive Hail Storm Ever Known in Iowa.” In width, the storm ranged from a half-mile to two-and-a-half miles and affected one-hundred-and-twenty-five miles of land. Many farmers’ crops were destroyed.

“Small grain in the track of the storm was leveled to the ground and the grain literally beat off the heads. Corn fields show that even hail storm[s] have queer freaks; one portion of the field would be leveled to the earth, pounded and battered to tatters.” The other part of the field would still have the corn stalks standing straight and tall, “every leaf stripped off of them.”

After the hail, rain fell and pushed the hailstones into piles, some of which affected the railroads. The train between Gray and Manning was forced to halt in its journey north. Beyond the obstacle of the hail on the tracks, the hailstones’ impact also broke glass in the coach and baggage cars of the train.

This weather event was significant enough to be reported in The Fairfield Tribune in Jefferson County, two counties south and seven east of Audubon. However, none of the reports say how the Meskwaki fared during the storm though, in 1883, they also resided in Audubon County. Reports from the period tell us that the Meskwaki and the white settlers both lived in Audubon county in the summer months. The Meskwaki travelled from Tama County to hunt in Audubon County during the summer until 1886.

After being banished from their home land in the 1840s, the Meskwaki were forced to live in Kansas until 1857. On July 13, 1857, the Meskwaki purchased 80 acres in Tama county back from the U.S., re-establishing their formal presence in the state of Iowa. There is a strong probability that the Meskwaki, prior to being banished from Iowa, had hunted in the lands that were to become Audubon County. But, the 1915 History of Audubon County states that “there is nothing to indicate that the Indians ever made permanent homes in this county.” The county history claims this primarily because at that time no one had found any remains of a town there. However, the county history does concede that this was probably always a native summertime hunting ground. “In summer when food for wild animals and birds was abundant, this must have been the Indian hunter’s paradise,” the county history states.

In one incident, some of the Meskwaki were having great success hunting deer in the area. But the white settlers felt they controlled the game in Audubon County. One of the settlers, Huntley, “drew the profile of an Indian with charcoal on the bark of a tree; then pointing to the picture said: “Him Indian! Indian kill white man’s buck! White man skuddaho (whip) Indian like h—l! Puckachee (go away)!” He then drew a revolver and shot at the picture.” The Meskwaki left the hunting grove the next morning.

The author of the History of Audubon County, Iowa, H.F. Andrews, was a member of this party. In retrospect, he wrote, “I have since thought that we treated the poor savages worse than the occasion required.” However, his regret is short lived, as in the second half of the same sentence he writes, “but it was an aggravation for them to come into our settlement and kill game under our noses.”

While the reports of specific nineteenth-century weather events do not typically include the native perspective, there are other ways of understanding Native Americans’ relationship with the weather. In fact, the origin story of the Meskwaki begins with a storm, in which He-nau-ee (the mother from whom all Meskwakis come) comes down from the Upper World. The storm is described as one that “has not been before or since,” in which “the sky and the sea struck each other, and the rocks were ground into sand.”

Today, poet Ray Young Bear of the Meskwaki keeps the Native American connection to nature alive in his poetry. In his collection The Rock Island Hiking Club, is the poem “The Mask of Four Indistinguishable Thunderstorms.” Though the Meskwaki connection to the hail storm on August 8, 1883 is unclear, perhaps they had sentiments similar to those Ray Young Bear expresses in the following lines from his poem.

“It is the thunderstorm

at first

that begins speaking

from an easterly direction

We listen to its vociferous

non-threatening

voice and fall asleep

This weather doesn’t care

to know itself

our inner physical journals

record

We assess: icy rain is no different

than wet branch-breaking

snow and the summer deluge

that stretches

toward autumn combines all into one

haunting answer

That of a wintry inevitability

glazed ice

over the terrain

The symphony

Before awakening we hear clouds

that quietly explode

from within

Watery moonlit fragments hit

the roof

saying: in case of anger

fist-sized hail would splinter

everything”