Cause or Coincidence? Inundation and Disease, 1952

Sioux City, Woodbury County, Iowa

Barbara Eckstein

1952

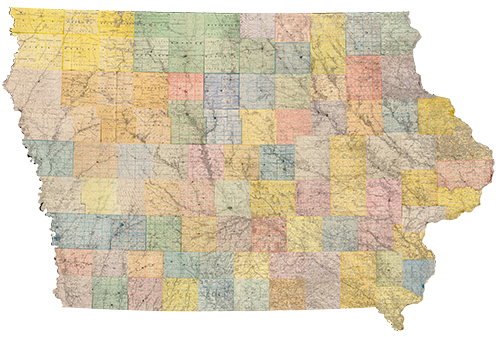

In 2014, senior hydrologist Jeff Zogg with the National Weather Service out of Des Moines issued a report about the five worst Iowa floods to date. Rather than base his conclusions on numerical data alone, he created the list by combining rankings of floods by six Iowa meteorologists and hydrologists who relied on their opinions, experience, and historical information to make their choices. The weather experts were unanimous in their designation of 1993 and 2008 as numbers one and two on their 2014 list, but for number five there was a tie between the 1952 Missouri River flood and the 1965 Mississippi River flood (described in the eastern counties of PWM).

Like all weather events, the damage wrought by the 1952 Missouri River flood was a product of the human conditions and climate of its time. The system of dams agreed upon in the U.S. Flood Control Act of 1944 for the upper Missouri River and its tributaries had not yet been completed. The winter snow pack had been considerable and the cold severe, but then an abrupt warm spell in March melted the snow quickly sending it into the river. The dams, not yet completed, could not mitigate the effects of the resulting flood.

Sioux City and surrounding agricultural lands in Woodbury County as well as other cities and farmlands from South Dakota to beyond Omaha, Nebraska, suffered considerable damage. $43 million ($380 million in 2013 inflation-adjusted dollars) was the final cost of the destruction, half of that in urban areas and half damage to agriculture.

But there was a yet greater cost to Sioux Citians in 1952: disease followed the flood. In January of 1953 The Sioux City Journal reported that in the summer of 1952, the city experienced the worst poliomyelitis epidemic ever. While in 1951 there were 74 reported cases and 2 deaths and in 1953 there were 86 reported case and 2 deaths, in 1952 there were 923 reported cases of polio and 53 deaths.

These are shocking numbers and must have given the city’s residents reason to consider the relation, if any, between the significant flood and the spike in polio cases. One thing for sure, Sioux City was not alone in their battle against the virus. “The year 1952 was the worst polio year on record [in the U.S.], with more than 57,000 cases nationwide….Twenty-one thousand victims suffered permanent paralysis and about 3,000 died….The 1952 [polio] season started before Memorial Day, gained ferocious momentum in the summer months, and pushed well into October.” Of course, the whole nation had not experienced a massive flood, so perhaps the flood and the epidemic were not connected. In addition, those who study the spread of disease note that polio was unusual in seeming to target those in nations with safer, more robust water and sanitation systems and better health care, places where a vast part of the population had not been exposed to the virus early in life with little harm and a very helpful subsequent immunity. Isolated, mostly healthy communities, ironically, seem to have been particularly vulnerable, such as during the 1952 epidemic. Sioux City might well have fit that description.

In fact, “polio hit the Iowa farmbelt hard in the summer of 1952.” One especially tragic story concerns the Thiel’s, a farm family who lived outside Mapleton, in Monona County just south of Woodbury Co. Eleven of the fourteen children in the family came down with polio; nine recovered but two were left paralyzed. Isolated, the children seem to have been especially vulnerable when their older siblings returned to the farm having been in military training at Fort Riley, Kansas, and working at “St. Joseph’s Hospital in Sioux City, site of the region’s largest polio ward.”

And yet what is known about the spread of the virus suggests some reason to connect it, in Sioux City, to the March flood. “Polio is an enteric (intestinal) infection, spread from person to person through contact with fecal waste: unwashed hands, shared objects, contaminated food and water.” The flood pushed city residents into more communal work and living spaces and more sharing of objects, food, and water with less control over sanitation. The flood may have been one factor that produced 923 Sioux City cases of polio in the summer of 1952 exposing Joan Thiel at St. Joseph’s and then her siblings on the farm.