Grasshoppers and the Weather

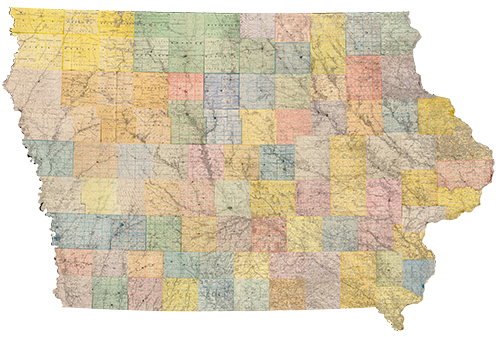

Rock Rapids, Lyon county, Iowa

The History of Doon, like other histories of Lyon (formerly Buncombe) County, refers to the period 1873-1883 as “the plague years.” Those were the years that swarms of grasshoppers brought settlement to a near standstill. Although the grasshoppers left the prairie alone, they attacked grainfields, gardens, fabric, and people. They got in houses and wells. So many grasshoppers died on the railroad tracks that, at one point, the rails were declared too slick to use safely.

The History of Doon, like other histories of Lyon (formerly Buncombe) County, refers to the period 1873-1883 as “the plague years.” Those were the years that swarms of grasshoppers brought settlement to a near standstill. Although the grasshoppers left the prairie alone, they attacked grainfields, gardens, fabric, and people. They got in houses and wells. So many grasshoppers died on the railroad tracks that, at one point, the rails were declared too slick to use safely.

The county offered 5 cents per quart for their capture, the state legislature allotted $75,000 to settlers for eradication of grasshoppers and reseeding, and the U.S. Congress, in 1873-74, granted homesteaders an extension on their allotments if they wanted to go east until “the plague” cleared. Some later claimed that the $75,000 went to the wealthiest landowners and not the poor settlers who most needed it. Bonnie Doon, Our Town claims that only 20 thousand of the 400 thousand acres of Lyon County had even been made available to homesteaders; the rest went to the railroad and speculators, including Governor Larabre.

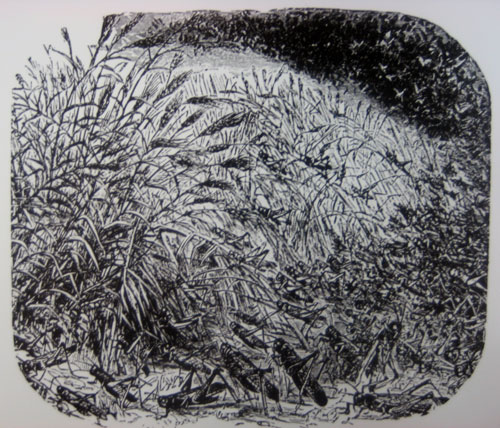

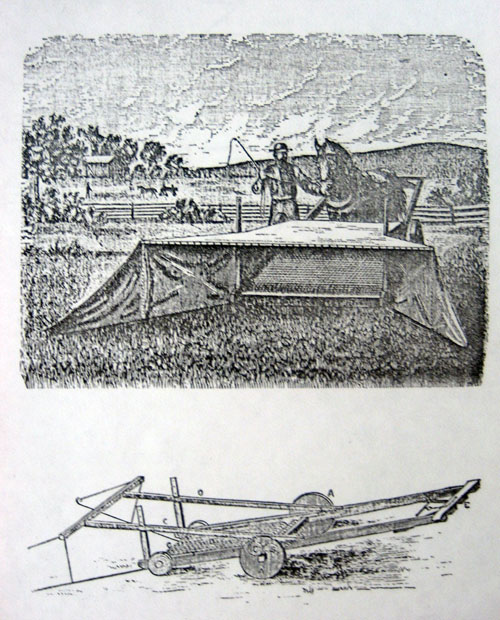

Even so, the description of the swarms makes clear why the governments at all levels would have reacted to “the plague” somehow: At 5 p.m. on Friday, July 25, 1874, for example, a swarm described as covering a territory from Little Rock to Sioux Falls and north to LuVerne, Minnesota, descended to the ground. They remained until 10 a.m. on Sunday when they all rose at once, turning the sky black and leaving behind empty fields and gardens and fouled wells. Laura Ingalls Wilder similarly describes, in her book On the Banks of Plum Creek, a swarm of grasshoppers that destroyed her family’s wheat crop in southern Minnesota. Those Lyon County settlers who had stayed fought back with nets and homemade devices, pulled through the fields, that scooped the insects into coal tar that trapped them there. By 1888, the grasshoppers were declared gone from the county.

Even so, the description of the swarms makes clear why the governments at all levels would have reacted to “the plague” somehow: At 5 p.m. on Friday, July 25, 1874, for example, a swarm described as covering a territory from Little Rock to Sioux Falls and north to LuVerne, Minnesota, descended to the ground. They remained until 10 a.m. on Sunday when they all rose at once, turning the sky black and leaving behind empty fields and gardens and fouled wells. Laura Ingalls Wilder similarly describes, in her book On the Banks of Plum Creek, a swarm of grasshoppers that destroyed her family’s wheat crop in southern Minnesota. Those Lyon County settlers who had stayed fought back with nets and homemade devices, pulled through the fields, that scooped the insects into coal tar that trapped them there. By 1888, the grasshoppers were declared gone from the county.

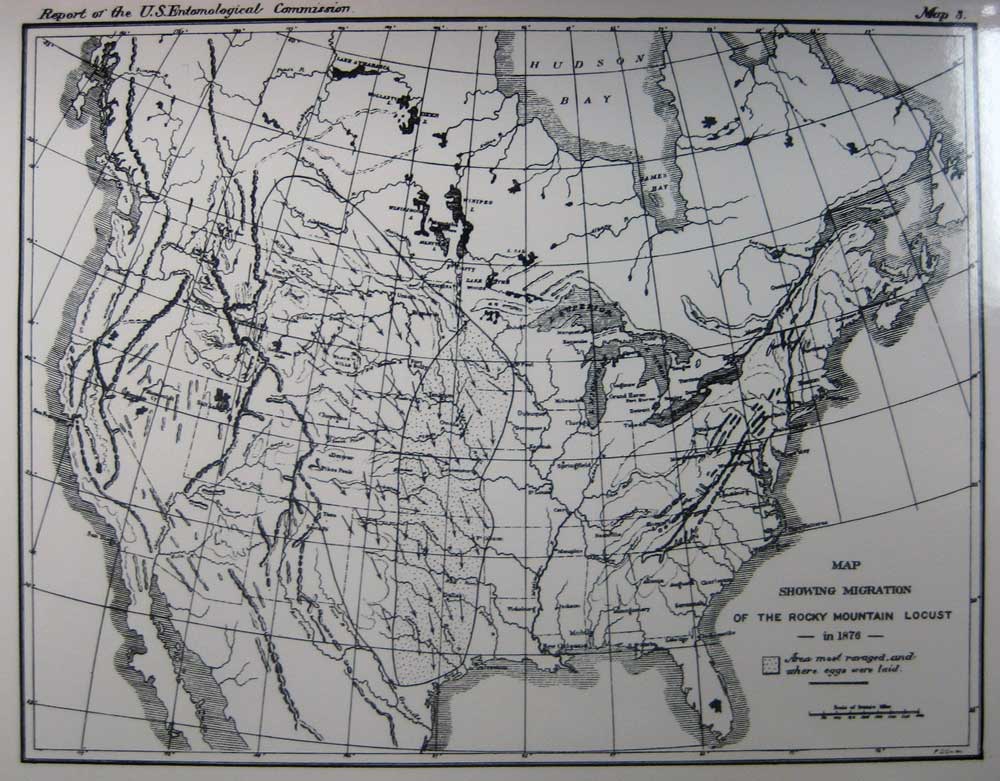

In fact, by 1902, one likely species implicated in the Lyon County trouble—Rocky Mountain locust (Melanoplus spretus)—were all but extinct. That’s the last year one was seen, in southern Canada. In 2014, the Rocky Mountain locust was declared officially extinct by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Grasshoppers—locusts—played a large role in the history of Lyon County, but was their presence in “the plague years” connected to the weather? Jeff Lockwood, entymologist at the University of Wyoming and author of Locust: The Devastating Rise and Mysterious Disappearance of the Insect that Shaped the American Frontier (Basic Books, 2004), says, almost certainly yes. Jeff Lockwood told PWM that “the large-scale population dynamics of this species [Rocky Mountain locust (RML)] were most surely driven by weather. Of course, at a local level the locust would select particular areas for feeding and egg-laying. So it’s likely that the green fields were more attractive to the insects than the adjacent prairie. However, RML outbreaks did not persist for periods of 16 years, so in at least some of the years [1872-1888] M. spretus was almost surely not involved, but some other grasshopper species was the culprit.The population dynamics of these other species were a function of both weather and food availability (as well as predators, parasites and pathogens). Even so, all grasshopper species are, to some extent, influenced by the weather (which directly affects the rate of development which can be key in terms of survival to adulthood and often indirectly affects mortality; for example, high rainfall is conducive to fungal [diseases]). The weather almost certainly played a substantial role in the population dynamics of the grasshoppers infecting Iowa fields—whether a strong, large-scale influence (RML) or a more local influence (for example, other species of Melanoplus that were not locusts and persisted in a region over time rather than travelling in swarms). That said, the presence of crops almost surely played a role as well in providing the insects with nutritious, green food.”

Grasshoppers—locusts—played a large role in the history of Lyon County, but was their presence in “the plague years” connected to the weather? Jeff Lockwood, entymologist at the University of Wyoming and author of Locust: The Devastating Rise and Mysterious Disappearance of the Insect that Shaped the American Frontier (Basic Books, 2004), says, almost certainly yes. Jeff Lockwood told PWM that “the large-scale population dynamics of this species [Rocky Mountain locust (RML)] were most surely driven by weather. Of course, at a local level the locust would select particular areas for feeding and egg-laying. So it’s likely that the green fields were more attractive to the insects than the adjacent prairie. However, RML outbreaks did not persist for periods of 16 years, so in at least some of the years [1872-1888] M. spretus was almost surely not involved, but some other grasshopper species was the culprit.The population dynamics of these other species were a function of both weather and food availability (as well as predators, parasites and pathogens). Even so, all grasshopper species are, to some extent, influenced by the weather (which directly affects the rate of development which can be key in terms of survival to adulthood and often indirectly affects mortality; for example, high rainfall is conducive to fungal [diseases]). The weather almost certainly played a substantial role in the population dynamics of the grasshoppers infecting Iowa fields—whether a strong, large-scale influence (RML) or a more local influence (for example, other species of Melanoplus that were not locusts and persisted in a region over time rather than travelling in swarms). That said, the presence of crops almost surely played a role as well in providing the insects with nutritious, green food.”

The weather, the breeding and feeding patterns of the insects, and the land use patterns of new humans in the county worked together to produce, for a few years, the swarming of what was probably the Rocky Mountain locust and the continued presence of other grasshopper species in the county. The Lyon County grasshopper story is like most stories about the weather; whatever damage the weather may cause, the weather culprit rarely acts alone.