Why It’s Called the “Big Muddy”

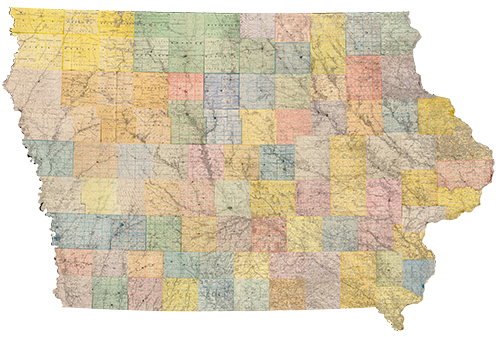

Council Bluffs, Pottawattamie county, Iowa

Emma Husar

3/29/1881

The Missouri River, the “Big Muddy,” the border separating Iowa from Nebraska,Council Bluffs from Omaha, rolls powerfully from the Upper Missouri River in the Rocky Mountains. The waters then meander through the lower Missouri River beginning just south of Yankton, South Dakota, until they meet the Mighty Mississippi. The Council Bluffs-Omaha region along the lower Missouri River had experienced a long history of fluctuations between seasons. Long before settlers came to this region, the water was washing to and fro around the bluffs and back into the river. “For centuries […] melting snows in the headwaters caused April floods, while snow-melt and rain caused June flooding. The annual flooding cycle created a rich ecology for the Missouri River basin […] that provided fertile breeding grounds for fish and fowl.” The settlers, in the spring of 1881, encountered the harsh realities of this history and were first to deem the cycle “destructive” to their way of life. Yet for convenience of the river and the beauty of the bluffs they stayed and built lives on the banks.

The Missouri River, the “Big Muddy,” the border separating Iowa from Nebraska,Council Bluffs from Omaha, rolls powerfully from the Upper Missouri River in the Rocky Mountains. The waters then meander through the lower Missouri River beginning just south of Yankton, South Dakota, until they meet the Mighty Mississippi. The Council Bluffs-Omaha region along the lower Missouri River had experienced a long history of fluctuations between seasons. Long before settlers came to this region, the water was washing to and fro around the bluffs and back into the river. “For centuries […] melting snows in the headwaters caused April floods, while snow-melt and rain caused June flooding. The annual flooding cycle created a rich ecology for the Missouri River basin […] that provided fertile breeding grounds for fish and fowl.” The settlers, in the spring of 1881, encountered the harsh realities of this history and were first to deem the cycle “destructive” to their way of life. Yet for convenience of the river and the beauty of the bluffs they stayed and built lives on the banks.

In the winter of 1880-81, especially near the upper Missouri River, “there was particularly heavy snow, and the primitive roads became impassable. Railroads were blocked with snow and could be cleared only with difficulty.” But this was only the beginning of the traffic jams. Once March came to a close, the temperatures in the upper basin rose above average. The snow was melting fast and had only one place to go: the Missouri River. The abrupt surge of water swelled toward the lower basin where temperatures had not yet increased and ice was still several feet thick.

Beginning in South Dakota and flowing towards Iowa, “ice dams and subsequent flooding […] resulted in the loss of thousands of cattle, [human] lives were lost and entire towns were destroyed.” This began a domino effect on March 29, 1881, though it did not hit Council Bluffs until April 6. And fortunately for Pottawattamie County, residents knew what was coming a few days before the flood arrived. They had been informed that upriver “Yankton had seen a 35 foot rise.”

A temporary dam was built, residents were urged to seek higher ground, and several were welcomed in by generous neighbors. The afternoon of the 6th came cascading and washed wide the divide between Council Bluffs and Omaha. That day the dam burst; “Omaha Smelting Works and Union Pacific Shops were almost completely submerged.” Soon after, “the floodwaters crested at 23.5 feet—two feet higher than ever recorded on the river.” The river broke the levee built to protect Council Bluffs against the flood waters, and its width grew daily and eventually separated the two cities by 5 miles. An eyewitness account on April 9th reported, “at one o’clock this morning the water was rising gradually in the river and pouring into the basins surrounding the lumber and coal yards in overwhelming streams.”

Railroads were submerged. Only occasionally rails that had once formed a bridge over the water could be seen skating across the waterline. Mid-April, trains from Chicago gained access to Council Bluffs to take passengers and mail from the disaster site, leaving those across the 5 mile, impassible expanse in Omaha stranded until the high tide ebbed.

Railroads were submerged. Only occasionally rails that had once formed a bridge over the water could be seen skating across the waterline. Mid-April, trains from Chicago gained access to Council Bluffs to take passengers and mail from the disaster site, leaving those across the 5 mile, impassible expanse in Omaha stranded until the high tide ebbed.

The water stayed for nearly all of April until it began to recede on the 27th. On April 25th in Council Bluffs, “600 people were homeless, with more than half of the city inundated with water.” In 1881, the Omaha Bee reported that at 23 feet and 4 inches above the low watermark, the river was “1 foot and 5 inches above the highest rise ever known.” When the 27th arrived, clean up commenced, people finally returned home; it was reported that the city had a few million dollars in damages.

Despite this level of damage, it was also reported that “the snail like pace at which the water [was] rising [robbed] it of the loss of life by which it would be marked, and gives time for the saving of much property—otherwise this mighty flood would rank also as a mighty disaster.”